Do Oncologists Believe New Cancer Drugs Offer Good Value?

作者:Eric Nadlera, Ben Eckertb, Peter J. Neumannb

【关键词】 Health,policy,•,Cost-benefit,analysis,•,Chemotherapy,•,Health,care,economic

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After completing this course, the reader will be able to:

Describe how academic oncologists view the costs of new treatments in their treatment recommendations.

Discuss academic oncologists’ perceptions of the cost and benefit of one new treatment in light of published results.

Describe how academic oncologists view the cost-effectiveness of new treatments relative to previously accepted standards.

ABSTRACT

Background. Substantial debate centers on the high cost and relative value of new cancer therapies. Oncologists play a pivotal role in treatment decisions, yet it is unclear whether they perceive high-cost new treatments to offer good value or how therapeutic costs factor into their treatment recommendations.

Methods. We surveyed 139 academic medical oncologists at two academic hospitals in Boston. We asked respondents to provide estimates for the cost and effectiveness of bevacizumab and whether they believed the treatment offered "good value." We also asked respondents to judge how large a gain in life expectancy would justify a hypothetical cancer drug that costs $70,000 a year. Using this information, we calculated implied cost-effectiveness thresholds. Finally, we explored respondents’ views on the role of cost in treatment decisions.

Results. Ninety academic oncologists (65%) completed the survey. Seventy-eight percent stated that patients should have access to "effective" care regardless of cost. Implied cost-effectiveness thresholds, derived from the bevacizumab and hypothetical scenarios, averaged roughly $300,000 per quality-adjusted-life-year (QALY). Only 25% of oncologists felt that bevacizumab offered "good value."

Conclusions. A majority of academic oncologists stated that cost does not influence their clinical practice, nor should it limit access to "effective" care. Yet respondents did not consider all effective drugs to be of good value. Implied cost-effectiveness thresholds were $300,000/QALY―a value higher than the $50,000 standard often cited. A subset of oncologists were sensitive to cost, believing it should factor into clinical decisions. These findings reflect the ongoing controversies within the medical community as expensive new therapies enter the system.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past 5 years, a number of innovative cancer treatments have entered clinical practice. The prices of many of these agents exceed $25,000 a year and result in benefits measured in months. The dramatic tradeoff between cost and clinical benefit has made their adoption a touchstone for broader debates over appropriate resource allocation in health care. The discussion over the high costs and relative value of new cancer medications has leaped from the podiums of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and pages of medical journals onto the business sections and editorial pages of the popular press [13].

Oncologists play a pivotal role in treatment decisions, yet little is known about the degree to which they believe that costs matter, or should matter, in their prescribing behavior. A few studies have attempted to ascertain physician views on cost-effectiveness and rationing [46]. To our knowledge, none to date have focused on new drugs for cancer, nor have they attempted to capture oncologists’ cost-effectiveness thresholds (i.e., beliefs about society’s willingness to pay) for new interventions.

In this paper, we report on a survey administered to practicing medical oncologists. Our goal was to understand oncologists’ views on the costs and value of new cancer agents and whether they believe there is a point at which incremental improvements in life expectancy do not justify the extra spending involved.

METHODS

Participants

We surveyed 139 clinical academic oncologists at Massachusetts General Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. Self-administered surveys were disseminated via departmental e-mail distribution lists that had been filtered to exclude oncologists not actively involved in patient care. We distributed the survey as an e-mail attachment that required physicians to print a hard copy in order to complete it. Physicians were assured of anonymity and asked to return the completed survey by mail or fax. One repeat mailing was sent 2 weeks following the initial mailing to ensure an adequate response rate. No incentives were offered to physicians to complete the survey. The survey instrument (available upon request) required approximately 5 minutes to complete.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire included four sections designed to examine the relationship between the costs of cancer therapy and treatment recommendations of oncologists and to assess oncologists’ perceptions of the value offered by new cancer treatments. A final section collected demographic and profession-specific information on respondents.

The first section of the survey asked oncologists to imagine a hypothetical, newly-approved medication for the treatment of metastatic lung cancer. Respondents were told that the new treatment cost $70,000 per year more than the standard of care treatment. They were then asked to identify the minimum survival benefit offered by the new medication at which they would be prepared to prescribe the new medication (respondents were told to assume no difference in quality of life). We presented survival benefits as categorical ranges (e.g., 24 months, 46 months), which spanned from a minimum of "1 day" to a maximum of "1 year +".

In section 2, oncologists were asked to provide estimates of the mean survival benefit and cost associated with the use of bevacizumab (Avastin®; Genentech, Inc., South San Francisco, CA) in advanced colorectal cancer (without referring to published information). We then asked oncologists whether they believed bevacizumab offered "good value for the money." Responses to this follow-up question were captured on a modified five-point Likert scale ("Yes Definitely" to "Definitely Not"). Based on this information, we calculated implied cost-effectiveness ratios for each respondent.

Section 3 of the survey explored the impact of new drug costs on oncologists’ treatment recommendations. Respondents were asked whether the overall cost of new cancer medications or the out-of-pocket costs faced by their patients influenced their treatment recommendations. Oncologists were also asked whether they believed every patient should have access to effective cancer treatments regardless of cost. Each response in this section was also recorded on a five-point Likert scale ("Strongly Agree" to Strongly Disagree").

Section 4 elicited oncologists’ beliefs about the future influence of drug costs on cancer treatment. A final statement gauged oncologists’ level of agreement (on the five-point Likert scale) with a statement that escalating drug costs would impose greater rationing in oncology care.

Data Analysis

We used oncologists’ responses in section 1 and section 2 to calculate implied cost-effectiveness ratios (C/E ratios) using the metric of dollars per quality-adjusted-life-year ($/QALY).

In section 1, incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated for each respondent according to the following formula:

where

Cost = $70,000;

LE = Life expectancy; the midpoint of the selected survival benefit range was used (i.e., if a respondent selected "24 months," a midpoint of 3 months was used);

QAo = Quality adjustment = 1 (i.e., no change in quality of life [QoL]).

A sample calculation (assuming the respondent selected a survival benefit range of 24 months) follows:

In our determination of this implied C/E ratio, we assumed the standard of care treatment would be one full year.

In section 2, C/E ratios were calculated using oncologists’ estimates of the cost and survival benefit associated with bevacizumab. Calculations were made in a manner similar to that described previously. In section 2, however, Cost is not a constant, and we make no explicit statement about QoL differences (though we assume no QoL differences in our calculation).

RESULTS

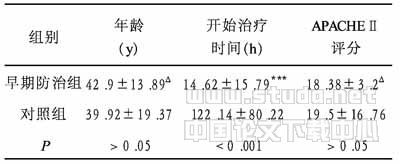

Of the 138 academic oncologists surveyed, ninety (65%) responded. The majority of respondents were male, the mean age was 42, and one half engaged in clinical activities <40% of the time (Table 1).

When asked if drug costs currently influenced their treatment recommendations, only 30% agreed or agreed strongly; 11% were unsure (Table 2). Seventy-eight percent of oncologists agreed that every patient should have access to "effective" cancer treatment regardless of cost. Although a majority of respondents did not feel that treatment costs would influence their clinical decisions, 81% stated that they would consider a patient’s "out-of-pocket" costs in their ultimate recommendations. When asked if costs would play a more important role in the next 5 years, two thirds of respondents concurred. Furthermore, 71% of oncologists believed that over the next 5 years, growing costs would impose greater rationing.

Sixty-two percent of respondents believed that a life-expectancy gain of at least 24 months justified the use of a hypothetical novel agent that cost $70,000 per year above the standard of care; an additional 20% felt 46 months would justify this cost (Table 3). The median implied cost-effectiveness ratio was $280,000 (Table 3). Only one respondent replied that 1 day of additional life would justify the $70,000/year cost, implying a cost-effectiveness threshold of $25,000,000/QALY ($70,000 divided by 1/365).

The average wholesale price of bevacizumab is approximately $4,400 per month and the overall survival benefit is approximately 4.7 months [7, 8]. In our study, 65% of oncologists surveyed underestimated bevacizumab’s survival benefit and 75% of physicians overestimated its cost, although in many cases misestimates were slight (Fig. 1). The mean implied cost-effectiveness threshold of bevacizumab, based on the responses of surveyed physicians, was approximately $320,000. Figure 1 plots each respondent’s estimates of cost and survival benefit, and identifies whether they considered the drug to be of good value. As the figures shows, respondents who thought bevacizumab did not provide good value tended to underestimate its survival benefit and overestimate its costs (p = .027.)

Table 4 stratifies the implied C/E ratios by respondents’ answers to selected questions about the role of costs from the hypothetical scenario. Respondents who believed costs influence their treatment recommendations had lower (p = .016) cost-effectiveness thresholds, that is, they believed that spending above $230,000/QALY would not be worthwhile (Table 4, first row). Respondents who believed that patients should have access to effective cancer treatments regardless of cost had higher thresholds ($345,000/QALY; p = .027) (Table 4, third row).

Univariate and multivariate analyses of the data; sex, gender, age, and percent of clinical practice, did not translate into statistically significant predictors of response.

DISCUSSION

Over the past decade, health care expenditures have continued to outpace gross domestic product growth [9]. Oncology care spending has grown faster than total health care spending, with chemotherapy serving as the largest driver of these increases [10, 11] As the medical and popular press increasingly focus on the rising cost of cancer care [10, 12], it is important to examine to what degree medical oncologists consider the cost of therapy in their clinical decisions.

A majority of medical oncologists in an academic medical setting stated that cost does not influence their clinical practice, nor should it limit patient access to "effective" care. However, when asked about specific scenarios, the oncologists implied that very small gains in life expectancy were not worth the costs.

New medical technologies are often evaluated with costbenefit or cost-effectiveness analyses [13, 14]. One common measure of cost-effectiveness is $/QALY. In the U.S., it is often cited that treatments with incremental $/QALY above $50,000 are not considered good value for the money [15]. Though this standard has murky origins, some point to Medicare’s decision to cover end-stage renal disease and dialysis, which had a cost-effectiveness threshold in that range [16, 17].

The implied thresholds we obtained were considerably higher than this standard. Oncologists may have different perceptions regarding value and benefit than other physicians, patients, and even society [18]. As specialists, we routinely face grave situations in which our treatments offer modest benefit. In oncology, it is not unusual to recommend therapies that offer survival gains that are measured in weeks rather than years. On the other hand, one might reasonably ask why oncologists’ thresholds were not $1,000,000/QALY or higher, given their statements that all patients should receive effective care regardless of costs. Our results could suggest that oncologists may have conflicted views on the subject. The majority of physicians surveyed required some minimum survival benefit measured in months to justify the cost.

Our data also suggest that physician perceptions of economic value do not correlate highly with their own practice patterns. Seventy-eight percent of surveyed oncologists believed that a patient should receive "effective" treatment regardless of cost. Yet when questioned if a therapy that has been shown in a randomized phase III trial to be effective offered "good value," the majority were unsure or disagreed. Oncologists will apparently offer therapy to patients regardless of whether they consider the treatment to be "good value," as long as it is considered effective. Interestingly, a few respondents underestimated bevacizumab’s survival benefit and overestimated its cost to be greater than $10,000 per month, yet still considered the drug to be a "good value," suggesting that some physicians’ knowledge on the matter is poor or that they have exceedingly high cost-effectiveness thresholds.

Academic oncologists seem to be a heterogeneous group with respect to their perceptions about costs. A small subset (approximately 15% in our sample) considered cost an important factor in their clinical decisions and had significantly lower C/E ratios than their colleagues. These respondents were not distinguishable by age, gender, or percentage of clinical work.

Although the majority of academic oncologists surveyed stated that they would not allow costs to influence their current clinical discussions and recommendations, they predicted that over the next 5 years, costs would become an increasingly significant factor in their practice. It is unclear from the survey if this anticipation is secondary to recent changes in reimbursement, the rising cost and number of new therapeutic agents, or the possible deployment of new cost-managing strategies. Regardless, physicians forecast that cost will become increasingly important in clinical decision making, even resulting in the "rationing" of oncology care. The survey did not assess whether oncologists believed that these cost considerations were good for clinical care or whether such influences would adversely affect clinical practice.

Our study has a number of limitations . First, the physicians surveyed practice in large, academic institutions and frequently participate in clinical trials that contain many of these new costly agents. It is possible that these physicians are more likely to recommend recently approved agents (so-called "early adopters") or value the benefits of these agents more than oncologists practicing in the community. Second, many of the respondents had clinical workloads that were substantially less than the average community oncologist. On the other hand, academic oncologists are often the first to use new therapies and are thus useful in predicting future trends in oncology care. In addition, patients seen in tertiary care centers are more likely to be referrals for second-line or later therapies. These patients may be more willing to try newer therapies with modest benefits than those patients seen in the community. This patient preference may manifest itself as a bias of academic oncologists and their valuations of new therapies. Finally, as with any survey, the manner we framed the questions may have influenced our results [19]. We tried to minimize bias through self-administration of the anonymous questionnaire and the wording of our survey.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite these limitations, our results offer some important conclusions. First, the majority of academic physicians surveyed believe that cost should not factor into their clinical recommendations, nor should cost limit a patient’s access to "effective" treatment. Second, although 78% of physicians would prescribe effective therapy regardless of cost, a majority did not believe that these therapies necessarily offered "good value." Third, although oncologists’ cost-effectiveness thresholds were significantly higher than those values previously held to be standard for clinical interventions, there was a minimum gain in life expectancy that physicians’required for costly treatment. Finally, physicians were clear that costs would likely become a more important factor in their practice in the near future. Oncology continues to undergo significant therapeutic breakthroughs, but these therapies are often associated with a high price. Central to any discussion of how these costs might figure into the future of oncology are the views of practicing oncologists, including those in academic institutions.

AUTHORS' NOTE

This research was performed without grant support. Our research was not funded by any external sources.

DISCLOSURE OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

Herper M. Cancer’s Cost Crisis. Forbes.com.

Alpert B. Tough Test: New Biotech Drugs Haven’t Been Subject to Cost-Effectiveness Reviews, But That May Change. Barron’s Online. Hershey JC, Asch DA, Jepson C et al. Incremental and average cost-effectiveness ratios: will physicians make a distinction? Risk Anal 2003;23:8189.

Holloway RG, Ringel SP, Bernat JL et al. US neurologists: attitudes on rationing. Neurology 2000;55:14921497.

Ubel PA, Spranca M, DeKay M et al. Public preferences for prevention versus cure: what if an ounce of prevention is worth only an ounce of cure? Med Decis Making 1998;18:141148.

Schrag D. The price tag on progress--chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;351:317319.

Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;350:23352342.

Altman DE, Levitt L. The sad history of health care cost containment as told in one chart. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;(Suppl Web Exclusives): W83W84.

Heffler S, Levit K, Smith S et al. Health spending growth up in 1999; faster growth expected in the future. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:193203.

Halbert RJ, Zaher C, Wade S et al. Outpatient cancer drug costs: changes, drivers, and the future. Cancer 2002;94:11421150.

Earle CC, Chapman RH, Baker CS et al. Systematic overview of cost-utility assessments in oncology. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:33023317.

Hunink M, Glasziou R, ed. Decision Making in Health and Medicine: Integrating Evidence and Values. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001:245305.

Muenning P. Designing and Conducting Cost-Effectiveness Analyses in Medicine and Health Care. San Francisco: Joseey-Bass, 2002:50203.

Neumann PJ, Sandberg EA, Bell CM et al. Are pharmaceuticals cost-effective? A review of the evidence. Health Aff (Millwood) 2000;19:92109.

Neumann PJ, Stone PW, Chapman RH et al. The quality of reporting in published cost-utility analyses, 19761997. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:964972.

Russell LB, Gold MR, Siegel JE et al. The role of cost-effectiveness analysis in health and medicine. Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA 1996;276:11721177.

Slevin ML, Stubbs L, Plant HJ et al. Attitudes to chemotherapy: comparing views of patients with cancer with those of doctors, nurses, and general public. BMJ 1990;300:14581460.

Ubel PA, Baron J, Asch DA. Preference for equity as a framing effect. Med Decis Making 2001;21:180189.