The Influence of Endocrine Effects of Adjuvant Therapy on Qu

【关键词】 Breast,cancer,•,Fertility,•,Gonadal,toxicity,•,Menopause,•,Quality,of,life

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After completing this course, the reader will be able to:

Identify risk factors for amenorrhea by age for young women treated with adjuvant chemotherapy.

Describe the associated quality of life outcomes with premature menopause as a sequelae of cancer therapy.

Discuss the safety and efficacy of fertility preservation options for women with breast cancer.

ABSTRACT

Significance. There are 2.2 million breast cancer survivors, and approximately 25%30% of newly diagnosed women each year are <50 years of age. Adjuvant therapy has prolonged survival, but the quality of that survival is influenced by persistent and late effects of therapy. Knowledge of treatment outcomes will assist in the design of interventions to prevent or manage persistent and late effects in survivors.

Purpose. The purpose of this paper is to review the incidence of gonadal toxicity associated with adjuvant chemotherapy, side effects of endocrine therapy, quality of life outcomes, fertility concerns, and options to preserve fertility in young (<35 years) and young midlife (3550 years) breast cancer survivors.

Results. Alkylating agentbased chemotherapy causes destruction of primordial follicles and impairment of follicular maturation resulting in temporary preservation of menses, reversible amenorrhea, irregular menses (perimenopause), or irreversible amenorrhea (ovarian failure―menopause). Younger women have a lower risk for amenorrhea with chemotherapy because of sufficient follicular stores, although the gonadal toxicity will result in an earlier than expected menopause. Premature menopause is associated with poorer quality of life, decreased sexual functioning, menopausal symptom distress, psychosocial distress related to fertility concerns, infertility, and uncertainty about late effects of premature menopause. Routine discussion about the menopausal experience, risks for infertility, and fertility preservation options is recommended.

Implications for Practice. This review identified adverse treatment outcomes for young and young midlife breast cancer survivors that can be minimized or prevented with targeted interventions.

INTRODUCTION

There are 2.2 million breast cancer survivors, and approximately 25%30% of newly diagnosed women each year are <50 years of age. With the lower mortality and longer survival time resulting from adjuvant therapy [1], chemotherapy or endocrine therapy may be recommended to women <50 years of age, depending on the stage, prognostic factors, and hormone sensitivity of the tumor. Late effects of adjuvant therapy were identified more than a decade ago [2], and the impact of persistent and late effects of cancer treatment on survivors has gained national and international attention [3, 4]. Younger women with breast cancer are more vulnerable to physical and psychological distress [5], and this greater vulnerability may account for the poorer quality of life outcomes that have been reported [6, 7]. There is variability in defining "young" in the breast cancer literature. In women’s health, young is a generally accepted description for women <35 years of age, with midlife beginning at age 35 [8]. This definition of young (<35 years of age) is consistent with published work in breast cancer that has addressed outcomes in younger versus older women [9, 10]. In this paper, young refers to women <35 years of age and young midlife women refers to those 3550 years of age.

This paper reviews the incidence of gonadal toxicity associated with adjuvant chemotherapy, side effects of endocrine therapy, quality of life outcomes in young and young midlife breast cancer survivors, fertility concerns, and options to preserve fertility.

OVARIAN FUNCTION AND CHEMOTHERAPY TOXICITY

Ovarian toxicity is a predictable side effect of alkylating agentbased chemotherapy and is influenced by the cumulative dose and duration of therapy [11]. Chemotherapy causes destruction of primordial follicles and impairment of follicular maturation [12]. The exact mechanism of ovarian damage is not fully understood, but in vitro studies suggest apoptotic changes in the pregranulosa cells that result in follicular damage [13]. The outcomes of ovarian damage from chemotherapy are dependent on the follicular reserve of the individual woman, which is age-related. Potential outcomes include follicular damage with preservation of menses, temporary amenorrhea, irregular menses (perimenopause), and ovarian failure (menopause).

Younger women who preserve their menses or who develop reversible amenorrhea will experience premature menopause but as a delayed effect rather than the immediate effect observed in older midlife women [13, 14]. For the average woman, the perimenopausal transition begins 35 years of age, and over the following 1015 years, there is a gradual decline in mature functional follicles and decreasing sensitivity to gonadotropin stimulation. These changes are characterized by alterations in bleeding patterns and cycle length, anovulatory cycles, and wide variations in hormonal levels [8, 15]. These transition changes explain the age pattern of amenorrhea and ovarian failure reported in women treated with chemotherapy for breast cancer. The risk for ovarian failure is substantially higher in women who are closer to the average age of natural menopause (51 years in white nonsmoking women) because of diminished follicular reserve.

The outcomes of women with chemotherapy-induced ovarian damage include menstrual changes, menopausal symptoms, changes in fertility potential, and infertility.

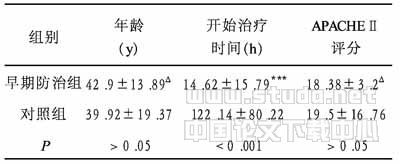

A considerable body of research has been published identifying the incidence, and variables of age, dose, and drug(s) associated with ovarian toxicity of adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer (Table 1) [14, 1628]. Age is a strong discriminating factor for ovarian failure [25]. In women <40 years of age who receive a three-drug combination of cyclophosphamide and fluorouracil with either methotrexate (CMF) or an anthracycline (CAF, FAC) for six to nine cycles, the incidence of amenorrhea ranges from 31%38%, and for women >40 years of age, the incidence of amenorrhea is dramatically higher. The time to develop amenorrhea also corresponds with age. Younger women (<40 years of age) develop amenorrhea in 48 months, compared with women who are older (>40 years of age) who can develop amenorrhea in 24 months on adjuvant chemotherapy. Based on the fact that higher cumulative doses and longer durations of therapy are associated with a greater risk for amenorrhea, the two-drug combination of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (AC) for four cycles was expected to result in less damage to the ovary. There are three studies (Table 1) [2628] that have explored the incidence of amenorrhea with four cycles of AC regimens with or without a taxane. The incidence of amenorrhea at 12 months was 14% in women <30 years of age and 33% in women aged 3040 years [27]. In another study, for women <40 years of age, the incidence of amenorrhea at 1 year was 15% [28]. Despite the fact that only one study collected prospective data [27], the findings of these studies suggest that four cycles of AC adjuvant chemotherapy with or without a taxane result in a slightly lower incidence of amenorrhea in younger women than six cycles of CMF. However, women >45 years of age who receive AC with or without a taxane have a >70% risk of becoming menopausal [26, 27, 29].

The return of menses following 12 months of amenorrhea after treatment in young women is not well documented [22, 23]. A recent prospective study suggests that there can be a return of menses after prolonged amenorrhea (>12 months), which raises issues about the appropriateness of a gynecologic workup to assess uterine pathology for unexplained vaginal bleeding [30].

SIDE EFFECTS OF ADJUVANT ENDOCRINE THERAPY

Young and young midlife women with hormonally sensitive breast cancer may receive endocrine therapy alone or following chemotherapy [31]. In addition to symptoms associated with the hormonal changes of induced menopause, endocrine therapy is also associated with a variety of other symptoms. Adjuvant therapy with tamoxifen (Nolvadex®; AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Wilmington, DE) has a symptom profile that includes vasomotor symptoms, vaginal complaints (dryness, itching, discharge), amenorrhea, insomnia, and mood disturbances [6, 27, 28, 3235]. Endocrine therapy with aromatase inhibitors is not recommended for women who become amenorrheic following chemotherapy because the amenorrhea may not be permanent and not reflect a true menopause [36]. However, there are clinical trials with aromatase inhibitors combined with ovarian suppression in premenopausal women [31]. Symptoms associated with aromatase inhibitors include hot flashes, vaginal dryness, bleeding and discharge, sleeping difficulties, fatigue, musculoskeletal complaints, headache, decreased libido, and breast tenderness [37, 38], all of which may negatively impact a woman’s quality of life [37, 39].

QUALITY OF LIFE IN YOUNG MIDLIFE BREAST CANCER SURVIVORS

Young and young midlife women with breast cancer are more vulnerable to psychosocial distress because of their developmental stage in life [5, 40, 41]. They may be single, married without children, parenting young to adolescent children, and establishing careers. The multiple demands of the cancer illness are layered on top of the multiple demands of a young woman’s life cycle, and women become more vulnerable to psychological morbidity as they attempt to manage multiple stressors [5, 42, 43]. Younger spouses experience emotional distress, have difficulty communicating about the illness and providing psychological support and often have difficulty carrying out household and childcare responsibilities [5]. Families with school-aged children who have a mother diagnosed with breast cancer are particularly vulnerable to poorer psychological outcomes [44, 45]. Experiencing premature menopause can further increase a young woman’s vulnerability, resulting in a greater risk for emotional distress and a poorer quality of life [6, 7]. Vulnerability was identified as the basic problem for young women diagnosed and treated for breast cancer who experienced premature drug-induced menopause [46]. This vulnerability was found to be related to physical and psychosocial distress associated with diagnosis and treatment, existential concerns, lack of adequate preparation for the menopausal experience, uncertainty, severity of menopausal symptoms, and changes in self concept. "Becoming menopausal" was a realization by women that menopause was more than the cessation of monthly menses. Women reported distress at the age inappropriateness of the abrupt menopause, uncertainty related to menopausal symptoms, uncertainty related to the temporary or permanent nature of amenorrhea, feeling older, having no peers to talk with about the experience, and loss of fertility. Young women report feeling different than other women their age, have concerns about early menopause, and describe multiple losses, including loss of menstruation and loss of fertility [46, 47].

There is an integral relationship among quality of life, chemotherapy-induced menopause, the menopausal symptom experience (from induced menopause and/or endocrine therapy), and sexuality for breast cancer survivors [6, 46, 4851]. Young women report worse emotional well-being, more psychological distress, higher anxiety, more unmet needs, and greater concerns about finances, work, and self-image than older women (Table 2) [7, 4042, 49, 5259]. Chemotherapy is associated with induced menopause and menopausal symptoms, which contribute to lower levels of physical functioning and poorer quality of life for young midlife women after breast cancer treatment [6, 40, 54, 56, 58, 6062]. Psychological distress is associated with the loss of menstrual function and loss of choice to have more children, even for those women who have completed their family planning, but is most significantly related to infertility for young women who have not yet started their families [46, 48, 56, 63].

Menopausal symptoms reported by breast cancer survivors include vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes, night sweats), fatigue, sleep disturbances, joint pains, dyspareunia, mood swings, cognitive changes, and vaginal dryness [34, 35, 51, 64, 65]. Although vasomotor symptoms and vaginal dryness are reported as the only true physiologic effects of estrogen withdrawal [66], there are data suggesting a neuroendocrine link to other symptoms, such as cognitive changes, mood swings, and related symptomatology, such as insomnia due to hot flashes. More severe vasomotor symptoms have been reported by breast cancer survivors [35, 64], and the suspected etiology is the abrupt change in the hormonal environment of women and rapid decrease in estrogen. Women’s emotional, physical, and functional well-being are negatively impacted by the persistence and severity of menopausal symptoms after treatment [6, 32]. Women with more severe menopausal symptoms who did not feel that they were adequately prepared for the chemotherapy-induced menopause experience reported greater uncertainty and psychological distress [67].

Young women who receive adjuvant chemotherapy and experience drug-induced menopause are at a greater risk for negative changes in sexuality and poorer sexual functioning outcomes [6, 48, 51, 6871]. As women gradually recover from therapy, sexuality and sexual function regain priority as a valued quality of life component [43, 63, 72]. Breast cancer survivors who received systemic adjuvant therapy report less sexual satisfaction than healthy women [73], lower levels of sexual function [68, 74], decreased libido [75], difficulty reaching orgasm, dyspareunia associated with vaginal dryness [71], and less sexual satisfaction [68, 71], and they don’t perceive themselves as feminine or sexually attractive as they did before treatment. Sexual functioning outcomes for women who receive adjuvant endocrine therapy are mixed, with some suggesting no effect [6, 33, 71] and others suggesting an adverse effect related to symptoms during therapy and the specific endocrine therapy taken [76, 77]. The negative impact of breast cancer treatment on the quality of life domain of sexuality for breast cancer survivors (Table 3) represents an important area for education, communication, support, and intervention, especially in younger women [43, 60, 65, 70, 74, 75].

FERTILITY

Uncertainty and Need for Contraceptive Counseling

Follicular damage resulting from chemotherapy is not an all-or-nothing phenomenon [13]. There is considerable uncertainty about the degree of damage because there is no way to measure follicular stores. If amenorrhea occurs, it may reverse, with a return to normal cycles, and those who develop irregular menses may subsequently ovulate in another cycle [78, 79]. Because of this variability and potential return of menstrual function even after a prolonged period of amenorrhea [30], serum hormone levels are not useful as predictors of permanent ovarian failure. Thus, contraceptive counseling is essential for women who experience menstrual changes associated with chemotherapy. Women on adjuvant endocrine therapy can become pregnant and should also be a targeted group for counseling. Pregnancy while on tamoxifen is not recommended because of possible teratogenic effects on the fetus, and women should be counseled to wait at least 12 weeks after discontinuation before attempting conception because of the half-life of the agent [80]. Barthelmes and Gateley [81] provide a review on the safety of pregnancy and tamoxifen. They identified six case reports of pregnancy in women on tamoxifen, an ongoing investigation by AstraZeneca of 50 known pregnancies associated with tamoxifen use, and a report of 85 women from the prevention trial who became pregnant. Of the six case reports, one case included a child with abnormalities of the genital tract, and an additional 10 children were reported to have fetal or neonatal disorders. Women must be informed of the potential effect of tamoxifen on the fetus and that there are no long-term data on possible late manifestations in children who were exposed in utero [81].

Desire for Pregnancy: Communication and Decision Making

The desire for biologic motherhood and genetically related children is an important issue for many cancer survivors [82, 83]. In breast cancer, many clinicians recommend that women wait to consider pregnancy for 23 years, when the highest risk for early recurrence has passed. Decision making about pregnancy in breast cancer survivors is associated with considerable uncertainty. Women have concerns about fear of recurrence and concerns about the potential effect of pregnancy on survival, and those who take endocrine therapy for 5 years have concerns about their fertility potential over time. In addition, there is a level of uncertainty among physicians about pregnancy after breast cancer treatment. A recent review of case control and cohort studies on pregnancy outcomes after breast cancer treatment suggests that there is no adverse effect on survival, but the authors conclude that there is still a lack of definitive evidence [84]. Breast cancer survivors who have successful pregnancies after treatment report that it helped normalize their life and the transition to wellness and that having children improved the quality of their lives [85].

Fertility Preservation

There is a recognized need to discuss fertility and options to preserve fertility before adjuvant chemotherapy for young women with breast cancer, yet women report that physicians described the side effects of therapy, but only one third to one half report that their concerns related to fertility were adequately discussed [82, 86]. In the U.S., there is a trend to marry later and to delay childbearing. If options to preserve fertility are not explored prior to treatment, the ovarian damage and subsequent premature menopause may prevent the possibility of a pregnancy after therapy. Potential options for fertility preservation include cryopreservation of oocytes, embryo cryopreservation with in-vitro fertilization (IVF), oocyte donation with IVF, ovarian tissue cryopreservation with IVF, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists to protect ovarian function [87, 88].

Cryopreservation of oocytes is not a viable option because of poor outcomes related to cryodamage of the oocyte in the process, and the exceptionally low pregnancy rate does not justify the use of this option for routine clinical practice [89]. In contrast, embryo cryopreservation with IVF is feasible, with established outcomes. For women with breast cancer, concerns and issues related to this option before the initiation of adjuvant therapy include the need for a partner or donor, compressed timing for decision making, potential risks of ovarian stimulation, and delay in initiating treatment because of the time required for ovarian stimulation and the IVF procedure [90]. Alternatives to standard ovarian stimulation have been investigated for women with hormonally dependent cancers. Tamoxifen with or without follicle-stimulating hormone [91, 92] and letrozole (Femara®; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ) combined with IVF have resulted in a good follicle yield, mature oocytes, and a sufficient number of embryos for cryopreservation [92]. These data should be considered preliminary, and further research is needed to verify the safety and efficacy of the approach. A second alternative, the use of a GnRH antagonist, was published as a case study of six women with cancer, four of whom were diagnosed with breast cancer [93]. The data suggest a potential role for the use of a GnRH antagonist for ovarian stimulation that reduces the duration of the fertility procedure and allows for earlier initiation of cancer therapy.

Ovarian tissue cryopreservation with IVF is an experimental procedure that includes harvesting ovarian tissue and implantation of the ovarian tissue followed by IVF. The feasibility of harvesting ovarian tissue has been established [13, 94], and preliminary data suggest that implantation is feasible [88, 90], but more research is needed on cryopreservation protocols, cryoprotectants, and transplantation techniques [89]. In July 2005, a case report was published of a successful pregnancy and birth in a woman with a history of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma using transplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue and IVF [95]. The authors state that they cannot rule out that the egg comes from the native ovary, but the patient’s 24-month history of amenorrhea following high-dose chemotherapy and laboratory data on the hormonal profile argue that the fertilization was related to the transplanted tissue. This initial case of a pregnancy in a cancer patient with transplanted tissue provides data to support continued investigation on the efficacy and safety of the approach. In addition to establishing the biologic feasibility, many other issues need to be addressed, such as the transfer of malignant cells, cost, insurance coverage, access, decision making, and long-term pregnancy outcomes and sequelae in women with a history of breast cancer.

The administration of a GnRH agonist during chemotherapy has been investigated as a method of protecting the oocytes and ovarian function. GnRH agonists act on the hypothalamicpituitary axis to suppress ovarian function, creating an artificial prepubertal hypogonadotropic state [12, 83, 96]. Data from nonrandomized studies with lymphoma [96] and breast cancer [97] suggest that administration of a GnRH agonist provides protection against gonadal toxicity, demonstrated by a resumption of menses in a high percentage of women. Two additional studies reported on the use of a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) analogue (goserelin [Zoladex®; AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals]) in women with breast cancer who received adjuvant therapy and reported a protective effect, with resumption of menses in 59%86% of the women treated [98, 99]. These initial findings suggest a potential role for the concept of gonadal quiescence.

In addition to biologic motherhood, parenting options should be included in the discussions of fertility. Surrogate pregnancy and adoption of a child are viable parenting options for breast cancer survivors.

SUMMARY

Ovarian failure in young and young midlife women who receive adjuvant chemotherapy with or without endocrine treatment is associated with poorer quality of life, decreased sexual functioning, menopausal symptom distress, psychosocial distress related to fertility concerns and infertility, and uncertainty about late effects of premature menopause, such as bone loss [2]. Health care providers need to more fully understand the experience of women with chemotherapy-induced gonadal damage. This review identifies the vulnerability of younger women diagnosed with breast cancer and the influence of premature, induced menopause on quality of life. The end of therapy is an emotionally distressing time for women, characterized by ambivalence, uncertainty, and anxiety as they attempt to transition from active treatment to survivorship [7, 57, 60, 63, 100, 101]. As treatment ends, women begin to recognize that menopause means more than a loss of monthly menses [4648]. Persistent menopausal symptoms are common [6, 32, 34, 64, 65], and the impact of menopause on sexuality and sexual function becomes more apparent.

Communication is central to cancer care delivery. Critical times for information preparation and discussion related to the acute, persistent, and late effects of gonadal toxicity include before treatment, at the end of treatment, and over the first year following adjuvant therapy. These times represent periods of high vulnerability for younger women with breast cancer. In addition to communication between the woman and her primary oncology providers, an interdisciplinary group of providers should be identified for appropriate referral to manage physical and psychological symptom distress and sexuality and sexual function problems, for fertility consultations, and for targeted interventions for healthy lifestyle behaviors aimed at risk reduction. Cancer treatment has prolonged survival, we now need to address the quality of life of those cancer survivors [3, 4].

DISCLOSURE OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author indicates no potential conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work has been supported in part by the American Cancer Society.

REFERENCES

Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Polychemotherapy for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomized trials. Lancet 1998;352:930942.

Shapiro CL, Recht A. Late effects of adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1994;(16):101112.

A National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship: Advancing Public Health Strategies. DHHS U57/CCU 623066-01. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta; 2004:169.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Living Beyond Cancer: A European Dialogue. President’s Cancer Panel. Bethesda, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, May, 2004:147.

Northouse L. Breast cancer in younger women: effects on interpersonal and family relations. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1994;(16):183190.

Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Desmond K et al. Life after breast cancer: understanding women’s health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:501514.

Ganz PA, Greendale GA, Petersen L et al. Breast cancer in younger women: reproductive and late health effects of treatment. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:41844193.

Fogel CI, Woods NF. Women’s Health Care. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1995:79100.

Albain KS, Allred DC, Clark GM. Breast cancer outcome and predictors of outcome: are there age differentials? J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1994;16:3542.

Yildirim E, Dalgic T, Berberoglu U. Prognostic significance of young age in breast cancer. J Surg Oncol 2000;74:267272.

Averette HE, Boike GM, Jarrell MA. Effects of cancer chemotherapy on gonadal function and reproductive capacity. CA Cancer J Clin 1990;40:199209.

Blumenfeld Z. Preservation of fertility and ovarian function and minimalization of chemotherapy associated gonadotoxicity and premature ovarian failure: the role of inhibin-A and -B as markers. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2002;187:93105.

Meirow D. Reproduction post-chemotherapy in young cancer patients. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2000;169:123131.

Partridge AH, Gelber S, Gelber R et al. Delayed premature menopause following chemotherapy for early stage breast cancer: long term results from IBSCG Trial V. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2005;16s:50s.

Voda A. Menopause, Me and You. New York: Harrington Park Press, 1997:1396.

Koyama H, Wada T, Nishizawa Y et al. Cyclophosphamide-induced ovarian failure and its therapeutic significance in patients with breast cancer. Cancer 1977;39:14031409.

Rose DP, Davis TE. Ovarian function in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Lancet 1977;1:11741176.

Samaan NA, deAsis DN Jr, Buzdar AU et al. Pituitary-ovarian function in breast cancer patients on adjuvant chemoimmunotherapy. Cancer 1978;41:20842087.

Padmanabhan N, Wang DY, Moore JW et al. Ovarian function and adjuvant chemotherapy for early breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 1987;23:745748.

Goldhirsch A, Gelber RD, Castiglione M. The magnitude of endocrine effects of adjuvant chemotherapy for premenopausal breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol 1990;1:183188.

Mehta RR, Beattie CW, Das Gupta TK. Endocrine profile in breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1992;20:125132.

Bonadonna G, Valagussa P, Rossi A et al. Ten-year experience with CMF-based adjuvant chemotherapy in resectable breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1985;5:95115.

Luporsi E, Weber B. The effects of breast cancer chemotherapy on menstrual function. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1998;17:155a.

Lower EE, Blau R, Gazder P et al. The risk of premature menopause induced by chemotherapy for early breast cancer. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 1999;8:949954.

Goodwin PJ, Ennis M, Pritchard KI et al. Risk of menopause during the first year after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:23652370.

Stone ER, Slack RS, Novielli A et al. Rate of chemotherapy related amenorrhea (CRA) associated with adjuvant adriamycin and cytoxan (AC) and adriamycin and cytoxan followed by Taxol (AC +T) in early stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2000;64:61a.

Swain SM, Land SR, Sundry R et al. Amenorrhea in premenopausal women on the doxorubicin (A) and cyclophosphamide (C)-docetaxol (T) arm of NSABP-30: preliminary results. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2005;16s:537a.

Fornier MN, Modi S, Panageas KS et al. Incidence of chemotherapy-induced long-term amenorrhea in patients with breast carcinoma age 40 years and younger after adjuvant anthracycline and taxane. Cancer 2005;104:15751579.

Ball J, Fox K. Age-associated incidence of chemotherapy-related amenorrhea (CRA) following adjuvant doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide and paclitaxel (AC/TAXOL) in early stage breast cancer. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2001;20:16a.

Sukumvanich P, Petrek JA, Naughton MJ et al. Incidence and time course of bleeding after long term amenorrhea following breast cancer treatment: a prospective study. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2005;16s:22s.

Dellapasqua S, Colleoni M, Gelber RD et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy for premenopausal women with early stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:17361750.

Couzi RJ, Helzlsouer KJ, Fetting JH. Prevalence of menopausal symptoms among women with a history of breast cancer and attitudes toward estrogen replacement therapy. J Clin Oncol 1995;13:27372744.

Ganz PA. Impact of tamoxifen adjuvant therapy on symptoms, functioning, and quality of life. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2001;(30):130134.

Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA. Menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum 1999;26:13111317.

Carpenter JS, Johnson D, Wagner L et al. Hot flashes and related outcomes in breast cancer survivors and matched comparison women. Oncol Nurs Forum 2002;29:E16E25.

Kudachadkar R, O’Regan RM. Aromatase inhibitors as adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal patients with early stage breast cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:145163.

Fallowfield L, Cella D, Cuzick J et al. Quality of life of postmenopausal women in the Arimedex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination (ATAC) adjuvant breast cancer trial. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:42614271.

Harwood KV. Advances in endocrine therapy for breast cancer: considering efficacy, safety, and quality of life. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2004;8:629637.

Baum M, Budzar AU, Cuzick J et al. Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early breast cancer: first results of the ATAC randomised trial. Lancet 2002;359:21312139.

Cimprich B, Ronis DL, Martinez-Ramos G. Age at diagnosis and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Cancer Pract 2002;10:8593.

Goodwin PPJ, Ennis M, Pritchard K et al. Association of young age and chemotherapy with psychosocial distress and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) during the first year after breast cancer (BC). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2004;22:732s.

Bloom JR, Kessler L. Risk and timing of counseling and support interventions for younger women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1994;(16):199206.

Sammarco A. Psychosocial stages and quality of life of women with breast cancer. Cancer Nurs 2001;24:272277.

Lewis FM, Hammond MA. Psychosocial adjustment of the family to breast cancer: a longitudinal analysis. J Am Med Womens Assoc 1992;47:194200.

Lewis FM, Zahlis EH, Shands ME et al. The functioning of single women with breast cancer and their school-aged children. Cancer Pract 1996;4:1524.

Knobf MT. Carrying on: the experience of premature menopause in women with early stage breast cancer. Nurs Res 2002;51:917.

Dunn J, Steginga SK. Young women’s experience of breast cancer: defining young and identifying concerns. Psychooncology 2000;9:137146.

Wilmoth MC. The aftermath of breast cancer: an altered sexual self. Cancer Nurs 2001;24:278286.

Avis NE, Crawford S, Manuel J. Psychosocial problems among younger women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 2004;13:295308.

Dow KH, Ferrell BR, Haberman MR et al. The meaning of quality of life in cancer survivorship. Oncol Nurs Forum 1999;26:519528.

Ganz PA, Coscarelli A, Fred C et al. Breast cancer survivors: psychosocial concerns and quality of life. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1996;38:183199.

Vinokur AD, Threatt BA, Vinokur-Kaplan D et al. The process of recovery from breast cancer for younger and older patients. Changes during the first year. Cancer 1990;65:12421254.

Mor V, Malin M, Allen S. Age differences in the psychosocial problems encountered by breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1994;(16):191197.

Ferrell BR, Grant M, Funk B et al. Quality of life in breast cancer. Cancer Pract 1996;4:331340.

Wang X, Cosby LG, Harris MG et al. Major concerns and needs of breast cancer patients. Cancer Nurs 1999;22:157163.

Spencer SM, Lehman JM, Wynings C et al. Concerns about breast cancer and relations to psychosocial well-being in a multiethnic sample of early-stage patients. Health Psychol 1999;18:159168.

Wenzel LB, Fairclough DL, Brady MJ et al. Age-related differences in the quality of life of breast carcinoma patients after treatment. Cancer 1999;86:17681774.

Arora NK, Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP et al. Impact of surgery and chemotherapy on the quality of life of younger women with breast carcinoma: a prospective study. Cancer 2001;92:12881298.

Kroenke CH, Rosner B, Chen WY et al. Functional impairment of breast cancer by age at diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:18491856.

Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL et al. Quality of life at the end of primary treatment of breast cancer: first results from the moving beyond cancer randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96:376387.

Hurny C, Bernhard J, Coates AS et al. Impact of adjuvant therapy on quality of life in women with node-positive operable breast cancer. Lancet 1996;347:12791284.

Schag CA, Ganz PA, Polinsky ML et al. Characteristics of women at risk for psychosocial distress in the year after breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:783793.

Schnipper HH. Life after breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:35813584.

Carpenter JS, Elam JL, Ridner SH et al. Sleep, fatigue, and depressive symptoms in breast cancer survivors and matched healthy women experiencing hot flashes. Oncol Nurs Forum 2004;31:591598.

Knobf MT. The menopausal symptom experience in young mid-life women with breast cancer. Cancer Nurs 2001;24:201210.

Utian W. The true symptoms associated with menopause confirmed after 33 years: better late than never, but let’s move on. Menopause Management 2005;14:78.

Knobf MT. The influence of symptom distress and preparation on responses of women with early stage breast cancer to induced menopause. Psychooncology 1999;8:88a.

Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Belin TR et al. Predictors of sexual health in women after a breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:23712380.

Lindley C, Vasa S, Sawyer WT et al. Quality of life and preferences for treatment following systemic adjuvant therapy for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1998;6:13801387.

Rogers M, Kristjanson LJ. The impact on sexual functioning of chemotherapy-induced menopause in women with breast cancer. Cancer Nurs 2002;25:5765.

Young-McCaughan S. Sexual functioning in women with breast cancer after treatment with adjuvant therapy. Cancer Nurs 1996;19:308319.

Knobf MT. Symptom distress before, during and after adjuvant breast cancer therapy. Dev Support Cancer Care 2000;4:1317.

Dorval M, Maunsell E, Deschenes L et al. Long-term quality of life after breast cancer: comparison of 8-year survivors with population controls. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:487494.

Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B et al. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: a follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:3949.

Barton D, Wilwerding M, Carpenter L et al. Libido as part of sexuality in female cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum 2004;31:599607.

Mortimer JE, Boucher L, Baty J et al. Effect of tamoxifen on sexual functioning in patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:14881492.

Bergland G, Nystedt M, Bolund C et al. Effect of endocrine treatment on sexuality in premenopausal breast cancer patients: a prospective randomized study. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:27882796.

Lo Presti A, Ruvolo G, Gancitano RA et al. Ovarian function following radiation and chemotherapy for cancer. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2004;113(suppl 1):S33S40.

Meirow D, Nugent D. The effects of radiotherapy and chemotherapy on female reproduction. Hum Reprod Update 2001;7:535543.

Goldhirsch A, Gelber RD. Life with consequences of breast cancer: pregnancy during and after endocrine therapies. Breast 2004;13:443445.

Barthelmes L, Gateley CA. Tamoxifen and pregnancy. Breast 2004;13:446451.

Partridge AH, Gelber S, Peppercorn J et al. Web-based survey of fertility issues in young women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:41744183.

Simon B, Lee SJ, Partridge AH et al. Preserving fertility after cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:211228.

Partridge A, Schapira L. Pregnancy and breast cancer: epidemiology, treatment, and safety issues. Oncology (Williston Park) 2005;19:693697; discussion 697700.

Dow KH. Having children after breast cancer. Cancer Pract 1994;2:407413.

Duffy LS, Greenberg DB, Younger J et al. Iatrogenic acute estrogen deficiency and psychiatric syndromes in breast cancer patients. Psychosomatics 1999;40:304308.

Dow KH, Kuhn D. Fertility options in young breast cancer survivors: a review of the literature. Oncol Nurs Forum 2004;31:E46E53.

Sonmezer M, Oktay K. Fertility preservation in female patients. Hum Reprod Update 2004;10:251266.

Falcone T, Attaran M, Bedaiwy MA et al. Ovarian function preservation in the cancer patient. Fertil Steril 2004;81:243257.

Oktay K, Sonmezer M. Ovarian tissue banking for cancer patients: fertility preservation, not just ovarian cryopreservation. Hum Reprod 2004;19:477480.

Oktay K, Buyuk E, Davis O et al. Fertility preservation in breast cancer patients: IVF and embryo cryopreservation after ovarian stimulation with tamoxifen. Hum Reprod 2003;18:9095.

Oktay K, Buyuk E, Libertella N et al. Fertility preservation in breast cancer patients: a prospective controlled comparison of ovarian stimulation with tamoxifen and letrozole for embryo cryopreservation. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:43474353.

Anderson RA, Kinniburgh D, Baird DT. Preliminary experience of the use of a gonadotrophin-releasing hormone antagonist in ovulation induction/in-vitro fertilization prior to cancer treatment. Hum Reprod 1999;14:26652668.

Radford J, Shalet S, Lieberman B. Fertility after treatment for cancer. Questions remain over ways of preserving ovarian and testicular tissue. BMJ 1999;319:935936.

Meirow D, Levron J, Eldar-Geva T et al. Pregnancy after transplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue in a patient with ovarian failure after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 2005;353:318321.

Blumenfeld Z, Eckman A. Preservation of fertility and ovarian function and minimization of chemotherapy-induced gonadotoxicity in young women by GnRH-a. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2005;(34):4043.

Fox K, Scialia J, Moore H. Preventing chemotherapy-related amenorrhea using leuprolide during adjuvant chemotherapy for early stage breast cancer. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2003;22:13a.

DelMastro L, Catzeddu T, Boni L et al. Temporary ovarian suppression with goserelin for prevention of chemotherapy induced menopause in young early stage breast cancer patients: results of a phase II study. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2005;16s:662a.

Recchia F, Sica G, De Filippis S et al. Goserelin as ovarian protection in the adjuvant treatment of premenopausal breast cancer: a phase II pilot study. Anticancer Drugs 2002;13:417424.

LaTour K. The breast cancer journey and emotional resolution: a perspective from those who have been there. In: Dow KH. Contemporary Issues in Breast Cancer. Boston: Jones & Bartlett, 1996:131142

Ward SE, Viergutz G, Tormey D et al. Patients’ reactions to completion of adjuvant breast cancer therapy. Nurs Res 1992;41:362366.

General References for Practicing Oncologists

1 A National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship: Advancing Public Health Strategies. DHHS U57/CCU 623066-01. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta; 2004:169.

2 Fallowfield L, Cella D, Cuzick J et al. Quality of life of postmenopausal women in the Arimedex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination (ATAC) adjuvant breast cancer trial. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:42614271.

3 Ganz PA, Greendale GA, Petersen L et al. Breast cancer in younger women: reproductive and late health effects of treatment. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:41844193.

4 Knobf MT. Carrying on: the experience of premature menopause in women with early stage breast cancer. Nurs Res 2002;51:917.

5 Simon B, Lee SJ, Partridge AH et al. Preserving fertility after cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:211228.