Current Shanghai Media Landscape in the Age of Globalization

(Abstract)

In the age of Globalization, information flow, like capital flow and commodity flow, takes place increasingly at the global level. As cross-border operations of various industries, including media industries, become increasingly frequent, nations become more and more interdependent. In this global environment and with China’s open and reform policies, in recent years, China has made great efforts for “letting the world know China better and letting China know the world better.” Shanghai as a large metropolis, naturally exhibits much enthusiasm in such efforts. The media form important channels for fulfilling this objective. This paper studies the current media landscape in Shanghai as waves of globalization lap the cultural seashores of various countries, with special emphasis on the issue of the media as channels for improving mutual understanding between China (Shanghai in particular) and the rest of the world. Furthermore, it explores the ways for better achieving this goal.

Keywords: globalization media development mutual understanding

I. Globalization and Global Communication

In recent years, globalization has become a buzzword with frequent appearance in the media, and has received much academic attention in various fields. The field of communication studies is no exception. A recent search by the writer on “Google.com” by entering the words “globalization and media” led to the links to 576 items. In the discourse of globalization, there does not seem to be a generally accepted definition of the term. On different occasions globalization is viewed as the free worldwide flow of the elements and resources of production, or as “stateless” or “borderless” economy, or as the economic, political and cultural integration of the whole world, or as Westernization… Opinions on what will be brought by globalization are divided as well. While some people tend to think that globalization will bring prosperity and progress to the whole world, others worry that it may bring poverty and cultural disaster to the developing countries.

Regardless of the different views and conceptions of globalization, the fact remains that nowadays, capital, commodities, technologies, services and so on can flow across national boundaries with increasing speed and ease, transnational corporations have global operations, and nations are now more and more economically interdependent. And “globalization” appears to be a convenient term for labeling such a phenomenon and the process in which this phenomenon is growing in prominence. Thus, it is no wonder that “globalization” is causing much discussion.

Even before the term “globalization” entered the academic as well as popular vocabulary in the 1990s, transnational corporations and global operations in various industries had existed and formed an important topic for academic studies. “Globalization” inevitably carries with it related problems, especially problems of imbalance in international trade and so on. In the world where different countries and regions exhibit different levels of economic and technological development and have different overall strengths, such imbalance easily occurs and has aroused a lot of concerns. In the field of communication, the phenomenon of the trading of media products in the international markets had long been a topic of much study. In 1983, for example, Hamelink showed his concern over the cultural autonomy of the developing countries in global communication (Hamelink, C., 1983); Mattelart discussed the extremely large market shares held by the transnational giants in the global communication markets (Mattelart, A., 1983). For another example, McPhail in 1985 discussed electronic imperialism (McPhail, T., 1985); Herbert Schiller in 1984 lashed at the spread of consumerist values by the transnational media corporations (Schiller, H., 1984)… Academic attention to global communication and related issues has continued throughout the 1990s and up till now.

Amidst various comments, the trend of globalization has persisted. And since the 1990s, this trend has been unfolding itself in multiple dimensions with greater momentum than before. In today’s communication landscape, we see media systems daily pouring large number of messages into the world; we find trans-border information flows increasing exponentially; we perceive media products being traded in the international markets with transnational media giants dominating such trade. Global communication, though certainly with its problems, has become an increasingly prominent phenomenon in the world today. This constitutes the broad, international environment in which current media development in Shanghai takes place.

II. Current Media Landscape in Shanghai

With China’s open and reform policies, media industries in China have grown rapidly in recent years. In Shanghai, media development is reflected, among other things, in the increased efforts in communicating to foreign audiences and in carrying out cooperation and exchanges with foreign media companies as well as in the increased number of newspapers and magazines published, the increased size of the newspapers (e.g., the size of the popular evening newspaper Xinmin Evening News has grown from 4 pages to 8 pages, then to 16 pages and then again to 32 pages), increased broadcasting hours, and growing diversity in media content. Statistics offered by China Journalism Yearbook 1998 indicate that in 1997 Shanghai published 80 newspapers, including the English-language newspaper Shanghai Star (a newspaper run by China Daily’s Shanghai office). Xinmin Evening News, which established an office in the United States in 1996, began to extend the distributions of its US edition to Canada as well in 1997. Altogether, the city published 1.934 billion copies of newspapers that year , showing a 2.2% increase over that of the previous year. So far as broadcasting hours are concerned, in 1997, Shanghai’s three TV stations, i.e., Shanghai TV, Oriental TV and Shanghai Education TV stations had a weekly broadcasting time of 389 hours, and Shanghai Cable TV Station had an average weekly broadcasting time of 605 hours (reaching 2,200,000 households); both showing some increase over that of he previous year. Starting from Feb. 1997, programs of Shanghai TV were brought to the Internet. The station’s English broadcasting service established some cooperative relationship with CNN in the United Sates, and a few dozens of English-language feature programs on China were broadcast through CNN’s global satellite TV network.[1]

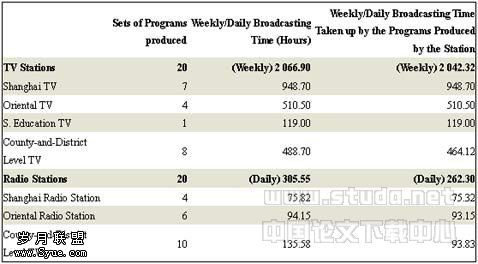

Five years later, in 2002, Shanghai’s media had further developed. The following statistics come from the official website of Shanghai Statistics Bureau:

TV and Radio Stations in Shanghai and Their Operations(2002) [2]

http://www.stats-sh.gov.cn/2003shtj/tjnj/2003tjnj/tables/17-24htm

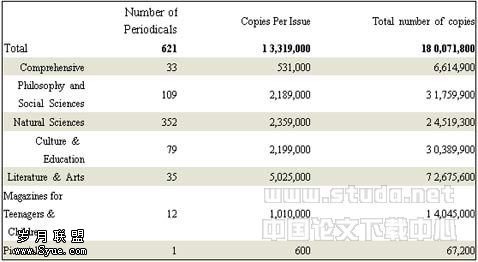

Number of Periodicals Published in Shanghai(2002) [3]

http://www.stats-sh.gov.cn/2003shtj/tjnj/2003tjnj/tables/17-36htm

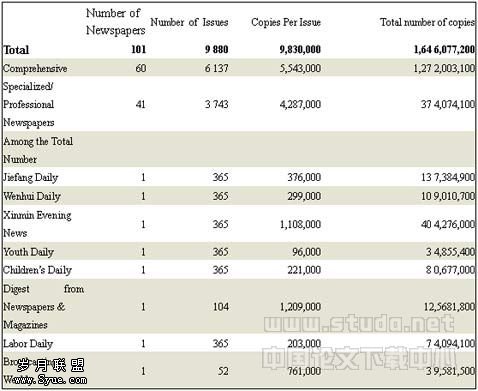

Newspapers Published in Shanghai (2002) [4]

http://www.stats-sh.gov.cn/2003shtj/tjnj/2003tjnj/tables/17-37htm

Compared with the case in 1997, the 2002 statistics show tremendous growth in the number of newspapers published in Shanghai and the weekly broadcasting time by Shanghai’s TV stations. Besides print and broadcasting media, Shanghai has also established many media website, among which Eastday.com is jointly established by 10 major media institutions in Shanghai. It has been operating since May 28, 2000. In addition, Shanghai currently has three media groups—the Wenhui-Xinmin United Press Group, the Jiefang Daily Group and Shanghai Media & Entertainment Group. Besides, with the development of satellite TV network, programs of the satellite channels of 11 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions of China are now available to audience in Shanghai.

Apart from the above-listed media institutions, many well-known foreign media corporations have set up their Shanghai offices in recent years. The writer’s surfing on the Net finds that the official website of the Foreign Affairs Office of Shanghai Municipal Government lists 51 foreign media organizations that have set up their Shanghai offices, including the US-based New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Dow Jones Newswires, Asian Wall Street Journal, Newsweek, Time, Business Week, Far-Eastern Economic Review and so on, the UK-based Financial Times, BBC, Reuters and Network Photographers, the Japan-based NHK, Nkhon Keizai Shimbun and so on, and some media organizations from Belgium, Germany, Russia, France, Finland, South Korea, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Singapore. With their operations in Mainland China, these Shanghai offices of foreign media may be described as one special scene in Shanghai’s media landscape. The website also mentions, besides these foreign media, the South China Morning Post of China’s Hong Kong Special Administrative Zone, which also has a Shanghai Office.

Shanghai has strengthened its efforts for international cooperation and international communication. Newspapers currently published in Shanghai include the English-language Shanghai Daily (local English-language newspaper of Shanghai officially launched in Sept. 2001) and Shanghai Star. They have their websites as well, thus making use of the Internet for reaching potential international audience in various parts of the world. Shanghai’s broadcasting media also have English-language news services. For example, the Oriental Broadcasting Network (satellite TV) airs the English news program “News at Ten”, Shanghai TV Station’s financial channel broadcasts “Shanghai Noon” as well as “News at Ten.” As Shanghai’s broadcasting media have established their websites, such programs are also available to potential worldwide audience. International cooperation is increasing for Shanghai’s media industries. In Dec. 2001, Shanghai Broadcasting Network (now called Oriental Broadcasting Network) reached an agreement with the Japanese TV company STV-Japan for telecasting in Japan programs of Shanghai Broadcasting Network. According to the agreement between the two sides, STV-Japan is responsible for the transmission of the programs of Shanghai Broadcasting Network. The target audience consists of Chinese living in Japan and ordinary Japanese with business relations with China or feeling interested in China’s affairs. [5] After Shanghai Media and Entertainment Group (SMG), a large media group for the broadcasting and film industries in Shanghai, was founded in 2001, it has enthusiastically promoted international exchanges between Shanghai’s broadcasting media and foreign broadcasters. In April this year (2003), SMG and CNBC Asia Pacific, a world-renowned business and financial news service organization headquartered in Singapore with its channels available in more than 25 million homes across the Asia Pacific region, signed an agreement to set up a strategic partnership. According to the agreement, SMG will provide Chinese business news for CNBC's television network, while CNBC will provide international business news for the financial channel of the Shanghai TV Station under SMG. Starting from April 14 this year, Shanghai TV Station has been producing two daily news programs for CNBC. Via connection through satellite links, these two brief Chinese business and finance news programs are broadcast on the TV network of CNBC Asia Pacific. Moreover, in line with the agreement, SMG has been airing a CNBC program about managers in Asia on Shanghai TV’s financial channel. Both SMG and CNBC Asia Pacific set great store by the partnership. Li, Ruigang, president of the Shanghai Media and Entertainment Group, which consists of TV stations, radio stations, newspapers and web sites and so on, remarks that this will be a win-win situation for the two sides, and Alexander Brown, president and chief executive officer of CNBC Asia Pacific points out that China is the most dynamic market in the Asia-Pacific region. [6] Mr. Wang, Lijun from Shanghai TV’s financial channel, one of the leading figures of this cooperative project, holds that through its strategic partnership with CNBC Asia Pacific, “SMG has acquired a platform for broadcasting news on a mainstream international TV network” to reach the audience in the Asia Pacific region.[7]

Through this strategic partnership, SMG and CNBC Asia Pacific are also cooperatively producing a program for airing on Shanghai TV’s financial channel.

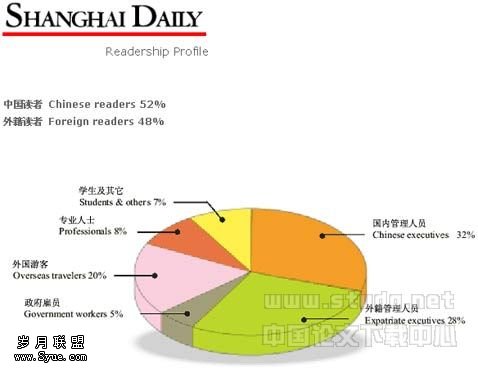

Discussion

From the sketch of Shanghai’s media landscape offered in the previous part of this paper, it can be seen that as a metropolis and the largest city in China, Shanghai has developed a diversified media network with print, broadcasting and online channels. And it holds the regional offices/branches of many world-renowned foreign media organizations. The city has shown an open-minded attitude in media development. This open-minded attitude is reflected in several aspects: (1) Providing English-language newspapers with online versions and English-language broadcasting media services (which are also brought online) for foreign audiences; (2) conducting international cooperation projects with Shanghai’s media institutions joining hands with foreign media organizations; (3) serving as the seat of many foreign media organizations’ regional offices/branches; and (4) regularly offering in Shanghai’s media information on foreign countries and their cultures. All these certainly contribute to Shanghai’s efforts in improving mutual understanding between China (Shanghai in particular) and the rest of the world. However, problems still exist in international communication by Shanghai’s media. For example, while foreign audiences are accustomed to the international journalism practice of emphasizing a diversity of sources in news and feature stories, it is not rare that stories in Shanghai’s English-language newspapers have limited sources. For another example, our media enjoy using governmental information sources as they are regarded as authoritative, yet a lot of foreigners, especially Westerners, tend to be skeptical towards governmental sources when they receive media messages. This discrepancy affects international communication. For still another example, Shanghai’s English-language media and English-language media services are clearly for communicating to foreign audiences unable to read Chinese, but the case in reality may be different from this expectation. A readers survey by Shanghai Daily in Sept. 2001 may serve to illustrate the point. The survey shows that the composition of the readership of this local English-language newspaper is as follows: [8]

Readership Profile

读者 Chinese readers 52%外籍读者 Foreign readers 48%

发行数量 Circulation 50,000 copies(数据来源:2001年9月《上海日报》读者抽样调查)(Source: Shanghai Daily Readers Survey, September 2001)

As globalization is featured by, among other things, fierce competition for international market shares, Shanghai’s media face an arduous task in studying the real international effects of their international communication. It appears that they need to ask, for example, such questions as: How large are sizes of the foreign audiences of Shanghai’s English-language newspapers and Shanghai media’s English-language broadcasting and online services? How well is the content provided by such newspapers and media services received among foreigners? How much do foreign audiences trust these information sources? Do Shanghai’s English-language media and media services compete successfully in the international mass communication markets with influential international media corporations with regard to China-related content?…

The results of Shanghai Daily Readers Survey in September 2001 show that asking such questions is by no means an unnecessary move. The survey demonstrates that as of 2001, more than half of the readers of this English-language newspaper are Chinese; foreign readers take up 48%. This does not appear to be satisfactory, as the fundamental reason for Shanghai to publish English-language newspapers, after all, is to enable foreigners who cannot read Chinese to learn news about China and about Shanghai in particular. So this represents one problem with Shanghai media’s foreign-oriented communication, i.e., communication activities meant for foreigners as the target audience. The survey results serve as a telling example to illustrate that Shanghai needs to study how to increase the proportion of foreign audience in the total audience of its English-language newspapers and broadcasting & online services. And it also needs to explore how to enlarge the audience size of such newspapers and broadcasting & online services so that they will really serve as influential news sources for worldwide audiences interested in China and the Chinese culture but unable to read Chinese.

To reach this goal, Shanghai’s English-language media and media with English-language services should make constant efforts in studying the international audiences, and the popular content and representation patterns of the most influential international media corporations. Foreign audiences, with their cultural backgrounds, values and accustomed patterns of media content and media representation patterns different from that of the domestic audience, may expect from Shanghai’s English-language media and media with English-language services patterns of information and information representation patterns that have not been thought of by these media and media services or that do not appear significant or that even appear bizarre to these media and media services. Therefore, only by carrying out constant studies of the foreign audiences will Shanghai be able to attract, with its English-language media and media with English-language services, more “eyeballs” in the international information markets. As Mr. Shen, Suru, an expert on international communication in China, observes, in international communication, “to make others know us better, we have to do our best to know others better.” [9] Studying the popular content and representation patterns of the most influential international media corporations will also help to make Shanghai’s foreign-oriented communication better adapted to the target audiences as such studies will help to reveal the foreign audiences’ accustomed patterns of media content and media representation patterns.

Moreover, it will be advisable for Shanghai’s media to strengthen their efforts in conducting international cooperation projects. Cooperation with world-renowned media organizations, in particular, will help Shanghai media to reach the international audience through the well-established channels of the latter’s global networks as the latter, with their long experience in international communication, their expertise in producing media products and their credibility among worldwide audience, can easily access the mainstream international mass communication markets.

International communication does not only mean foreign-oriented communication or foreign publicity. It also means providing domestic audience with information on foreign countries and foreign cultures. Shanghai’s media have been doing a lot for the latter as well. Foreign-related information, including foreign news, coverage of international sports events taken place in foreign countries and information on foreign cultures, forms a regular part of the media content in Shanghai. Shanghai being a metropolitan city, Shanghai people show a high degree of acceptance towards foreign cultures. Surveys by several Chinese scholars show that they tend to actively seek for foreign-related news and readily enjoy entertainment media products from different parts of the world.[10] For example, one survey in 1999 shows that “international news” in newspapers ranked very high as the frequently read content of the public in Shanghai: 61.3% of the respondents of the survey claimed that they frequently read “international news,” a higher percentage as compared with that of the respondents who claimed to frequently read “Shanghai News” (59.9%) and those who claimed to frequently read “National News” (53.0%). [11] The same survey finds that 45.6% of the respondents said that they frequently watched (on TV) films and teleplays produced in the United States; 21% of the respondents said that they frequently watched (on TV) films and teleplays produced in Japan. Another survey conducted in 2001 among the young people and teenagers even show higher percentage of the respondents who claimed to frequently watch (on TV) US-made films and teleplays (61.2%) and Japan-made films and teleplays(34.4%).[12]

While we should recognize the positive side of the flow of foreign-related information in Shanghai through the media for helping Shanghai people to acquire a better knowledge about foreign countries and foreign cultures, the possibility of some related problems should also receive attention. Some critics have pointed out that some imported TV cartoons contain violence and can have negative effects on children. [13] Besides, as media products, like other cultural products, inevitably carry with them cultural values, the latent effects of the products of foreign media cultures call for serious study. In addition, the results of the above-mentioned 1999 survey on citizens of Shanghai and foreign cultures appear to be puzzling with regard to the percentages of respondents who claimed to frequently read “International News,” “Shanghai News” and “National News” respectively, for these percentages contradict the journalistic wisdom summarized in one of the news values—proximity, which connects physical closeness to the appeal of news to the audience. And such results call for a study of the reasons behind them: Is it because Shanghai audience has become too world-oriented to take sufficient notice of the things taking place around them? Or is it because the content and representations of the content in “Shanghai News” and “National News” are not attractive enough to the audience? Or is ti because of some other reasons? Serious research regarding questions like these is worthwhile not only because it is necessary if Shanghai media are to improve their work, but also because in the age of globalization, media organizations are bound to face international competition. Already, some well-know foreign media organizations are publishing Chinese editions. And, with a lot of regional offices of foreign media organizations in Shanghai carrying out their activities, stories on Shanghai and on other parts of China written by journalists in such offices will pour into their home offices or Hong Kong offices for publication. Chinese editions of the foreign media and China-related stories written by reporters of the Shanghai offices of foreign media corporations will compete for the attention of audience in Shanghai as well as in other places. For Shanghai media to carry out more effective international communication amidst international competition, serious research on related issues will play an indispensable role.

To summarize, facing the international environment of globalization and carrying out the country’s open and reform policies, Shanghai in its media development has in recent years done a lot to improve mutual understanding between China (Shanghai in particular) and the rest of the world. But problems still exist in Shanghai’s international communication. And the effects of such communication are yet to be studied. It is considered advisable for Shanghai’s English-language media and media with English-language services to conduct systematic studies of the foreign audiences whose cultural backgrounds, values, and expectations towards media are different from the Chinese.

目录:

1. Hamelink, C. (1983). Cultural Autonomy in Global Communications. New York: Longman.

2. Mattelart, A. (1983) Transnationals and the Third World. Massachusetts: Bergin & Garvey.

3. McPhail, T. (1985) Electronic Colonialism. California: Sage.

4. Shiller, H. (1984).Information and the Crisis Economy. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

5. 沈苏儒《对外传播学概要》。今日出版社1999年版。(Shen, Suru (1999). China’s International Communication—A Theoretical Study. Beijing: China Today Press.)

6. 王立俊“国际主流电视网中的新闻直播平台”。上海《广播电视研究》2003年第四期第33-36页。(Wang, Lijun. (2003) “A Platform for Broadcasting News on a Mainstream International TV Network.” Shanghai Broadcasting Studies, No. 4, 2003, pp. 33-36.)

7. 张国良“上海市民与外来文化”。钟期荣主编《全球化与跨地区文化传播》。浙江大学出版社2003年版,第387-391页。(Zhang, Guoliang. “Citizens in Shanghai and Foreign Cultures.” In Zhong, Qirong (ed.)(2003). Economic Globalization and Cross-Regional Cultural Communication. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University Press. pp. 387-391.)

8. 《中国新闻年鉴1998》,第72-73页。(China Journalism Yearbook 1998, pp. 72-73.)

9. 上海市政府外办、上海统计局和上海文广局的网站上的有关信息。(Related information on the websites of the Foreign Affairs Office of Shanghai Municipal Government, Shanghai Statistics Bureau and Shanghai Broadcasting and Entertainment Bureau.)

注释:

[1] 《中国新闻年鉴1998》,第72-73页。(China Journalism Yearbook 1998, pp. 72-73.)

[2] [3] [4] [5] People’s Daily, Dec. 5, 2001. [6] People’s Daily, April 11, 2003. [7] Wang, Lijun. (2003) “A Platform for Broadcasting News on a Mainstream International TV Network.” Shanghai Broadcasting Studies, No. 4, 2003, pp. 33-36.) [8] [9] Shen, Suru (1999). China’s International Communication—A Theoretical Study. Beijing: China Today Press. p. 18. [10] Zhang, Guoliang (2001). “Citizens in Shanghai and Foreign Cultures.” (Unpublished article presented at an international conference.) In Zhong, Qirong (ed.)(2003). Economic Globalization and Cross-Regional Cultural Communication. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University Press. pp. 387-391. [11] Ibid. [12] Quoted in Zhang, Guoliang (2001). “Citizens in Shanghai and Foreign Cultures.” (Unpublished article presented at an international conference.) In Zhong, Qirong (ed.)(2003). Economic Globalization and Cross-Regional Cultural Communication. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University Press. pp. 387-391. [13]